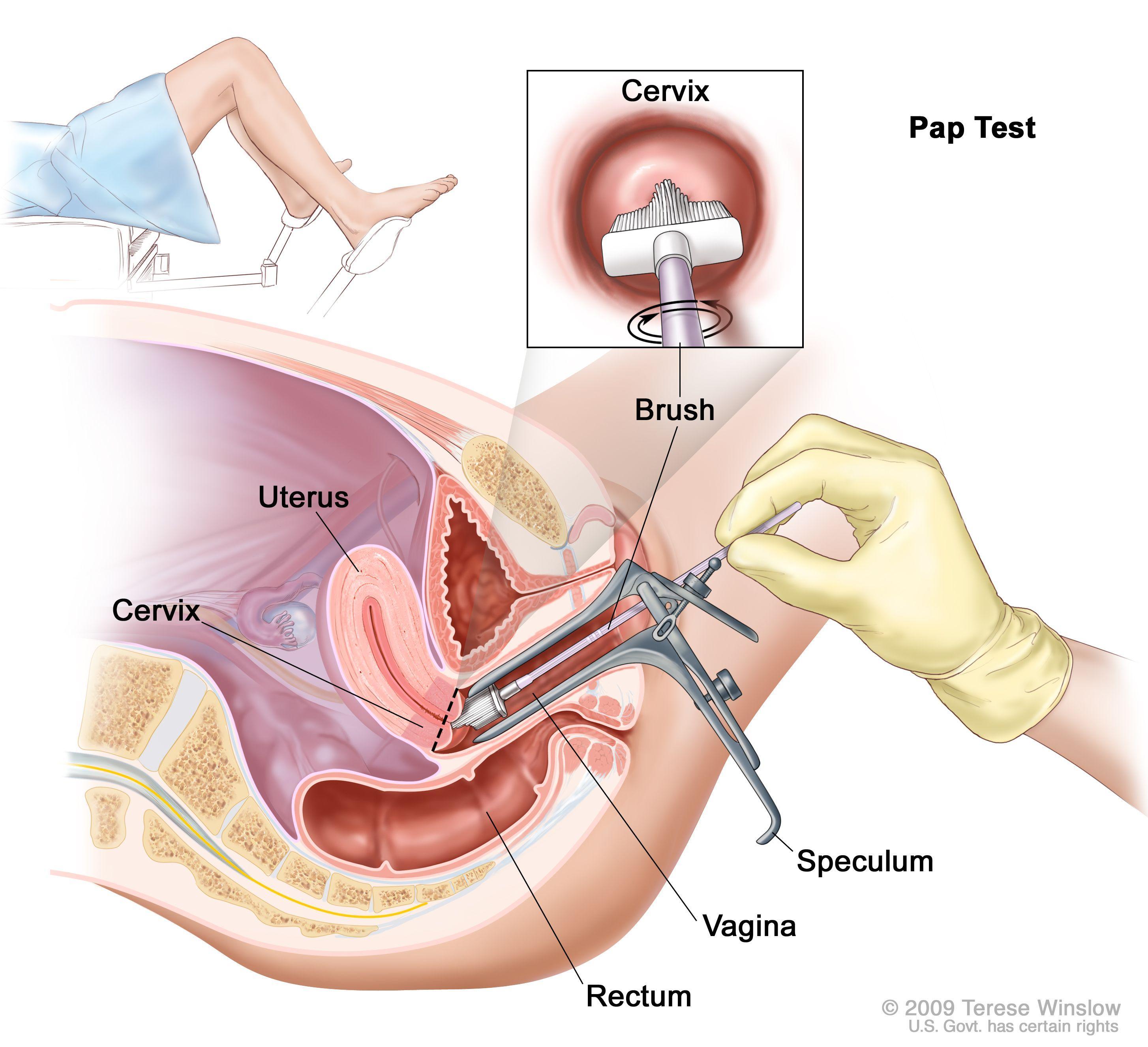

Regular Screening is Cervical Cancer Prevention

Screening is for healthy individuals with no symptoms. Cervical cancer screening helps to detect and treat cell changes at an early stage.

Regular testing can save your life and is the most effective method of preventing cervical cancer.